What makes a bad investment?

So when looking for investment properties you need to do the math (don't worry, it's easy) to figure out if you are on the right track. I'll walk you through the process I take when evaluating a house, but since there are 2,000 bad deals for every good one, I'll be lazy, take the easy way out, and walk through my thoughts on a horrible investment property.

Let's start with the property (through a listing on craigslist.org):

Ignore the poor English and terrible grammar for a second...$325000 INVESTMENT PROPERTY FOR SALE steps from Metro

6 MONTHS OLD LUXURY ONE BEDROOM CONDO RENTED OUT FOR $1450 PERMONTH TILL OCT 2007. STEPS FROM DUNLORING METRO. STAINLESS STEEL APPLIANCES, GRANITE COUNTER TOPS, SEPARATE LAUNDERY ROOM inside the unit, RENTED OUT TO VERY NICE COUPLE.

ALL THE AMENETIES YOU CAN THINK OFF POOL, GYM, MEDIA ROOM BASKETBALL COURT ETC CLOSE TO 495, 66, 29

CAN EMAIL PICS ON REQUEST. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION PLEASE CALL KAY AT 202-689-4256 I am a realtor working for FAIRFAX REALTY looking for buyer for this condo.

A 6 month old condo that has tenants? Either this is a strange flip, or an investment gone bad. Right now I'm going to guess the latter, that the original investors eventually realized what a bad investment the unit made and is now trying to bail. But we'll go ahead and continue our evaluation.

One of the first things I like to do when evaluating a new place is look at it on Google Maps. If you have an understanding of the area, this can be extremely enlightening. For example our property claims to be at the intersection of Prosperity Ave and Gallows Rd. By pulling it up in Google we can see that the area in question looks like this (the green arrow indicates the intersection):

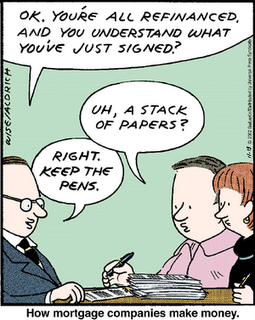

So the buyer seems to be asking for $325,000. Let's make a quick assumption that you, as an investor, are going to put 10% down. That leaves you with a mortgage of $292,500. At a decent investment mortgage rate of about 6.5% (investment mortgages are typically about 0.5% higher than mortgages for a personal residence), we have a monthly payment of.... Uh-oh. $1848.

That's more than $400 a month more than the rent the unit is currently generating.

Let's continue our investigation. I'm going to assume for a moment that we can get insurance to the tune of about $50 a month. It may be a little on the cheap side, but if you do your homework and wrap that insurance up with your personal home insurance and your auto insurance, I'm sure you can get a comparable rate. That brings our monthly costs up to $1898.

In Fairfax County property taxes are set at 0.0089%. Assuming the unit in question is appraised near the sell value, that puts our annual property taxes at $28292.50, adding another $241 to our monthly bill, bring our total up to about $2139 a month to own this thing.

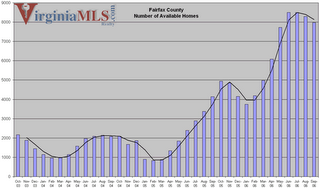

Since this is a condo, the association will charge a monthly fee to maintain the complex. These fees can vary wildly from building to building and aren't publicly advertised. The best place to get them is to look up the condo on google and try to find some resident complaining about the fees via a forum. Since I don't know the name of the complex, I can simply google "Gallows Rd Prosperity Ave condo".... and it looks like I hit the motherlode. The second link leads to a blog that I'm somewhat familiar with, referring to a condo at Dunn Loring called the Halstead. The link shows a wonderful picture depicting the number of units for sale in that particular project:

But we still don't know about the condo fees. Unfortunately further searching is fruitless. No specific information can be found. But after a little bit of googling I can estimate that the average condo fee for a 1-bedroom in Fairfax is between $200-$250 a month. Since this condo is extremely close to DC, I'm going to assume that the condo fee is on the high side of that, giving a new monthly total of $2389, but since most numbers in this article are approximations, we'll round it to $2400.

So if our numbers are somewhat in the ballpark, at the rate the current tenants are paying (until October 2007), we'd be losing $1000 a month to pay for this property.

Is the rent too low? Maybe the condo is in relatively poor shape and we can fix it up, or perhaps the condo is just being under rented. There are a variety of methods you can use to determine fair rent, such as craigslist, your local papers, etc. According to Rentometer.com, the median rent in our area for a 1 bedroom is only $1300. Proximity to the metro can easily explain why this property is earning more than the median, and when the tenant moved out, I wouldn't be surprised if we could easily get another $75-100 a month out of the place.

Adjusting rental prices to account for amenities is more of an art than a science. Amenities that could inflate rentals in one investment type, could do nothing to another. For example, when dealing with a one bedroom apartment, it's probably a waste of time to even look at school district information. Biff and I's townhomes, however, are located in the best school district of their county, which is a significant advantage for them. On the other hand, proximity to a college campus is more likely to raise the rents of apartment/condos than single family homes.

So what have we learned?

- At the current price, we'd have to expect about a $1,000 a month loss to maintain the property.

- The rent is already relatively fair and while we could probably milk a little more out of it, it's unlikely that we could get too much more.

- Given that the condo has a tenant and is only 6 months old, the seller is motivated. They either need the cash right now, or their "investment" is sucking the life out of them.

- Most likely, as learned through Google, condos in the area aren't selling very well and there is a very large number of them on the market.

So the final verdict? I actually like the area the condo is in. Being located across the street from the metro station is a tremendous asset that will help the unit's appreciation significantly over time. However right now the asking price is far too high. Given what we know about the condo, I think that there's no chance we could make a positive investment out of this unit.

Obviously I'm not surprised with the result. For one thing, there's no real way in which we can add value to the unit, short of dumping a tremendous amount of cash into the down payment. Not to mention that if you are looking for good investment properties, craigslist probably isn't where you want to start, especially with listings that scream GOOD INVESTMENT in their title. Those are usually anything but.

But just for recap, let's run over the important steps we took on this little path of discovery:

- Look up location on the internet, figure out distances to major highways and landmarks. Maps are invaluable. Even if you go there in person, unless you look on a map you might not realize that I-95 is just a minute away.

- Google the name of the complex. You never know what might turn up (like our photo above).

- Estimate your mortgage costs.

- Estimate your insurance costs.

- Research the local property taxes.

- Are there any condo or home owners association fees? Either research or estimate them.

- What rent can you get? Figure out local averages and then adjust for specific amenities.

- Compare the costs to the rental income